MALMEDY, BELGIUM, MISTAKEN BOMBING,

23 AND 25 DECEMBER 1944.

Prepared By:

Royce L. Thompson,

European Section, OCMH.

5 June 1952.

CONTENTS.

CRITIQUE.

Summary.

23 December.

Orders.

The Flight and Reports.

Photographs Identified MALMEDY.

Mistake Explanations.

24 December.

25 December.

Flight and Reports.

Mis-identification Reasons.

Allied Air Commanders' Conference.

DOCUMENTATION.

23 December.

- IXth BD Mission Summary, 23 Dec. 44.

- IXth BD Photo Interpretation.

- 322d BG OPFLASH Report.

- Pilot Interrogation Reports.

- 322d BG A-2 Log of Mission, 23 dec. 44.

- Orders.

- Maps.

- VIII.Weather Office of IXth

- 322d BG History.

- MALMEDY-ZULPICH Distance and Terrain.

- Route.

- Bibliography.

25 December.

- Formation for 25 Dec. 44, 387th BG.

- Interrogation Form of 387th. BG, 25 Dec.

- IXth BD Photo Interpretation.

- Unsatisfactory Bombing report

- Group’s OPFLASH, 252020 Dec.

- Overlay of Mission, by 387th BG.

- IXth BD Mission Summary, 25 Dec.

- VIII.IXth BD Mission Report.

- Eighth Air Force.

- Bibliography.

Appendix 1: 387th Dec. 23,24 & 25 1944

Appendix 2: 387th B Group

Appendix 3: 387th BG Missions Dec 1944

Appendix 4: 322d BG

Appendix 5: Bombardment Group organisation

Appendix 6: B26 images

Appendix 7: B-26 BOX Formation

Appendix 8: Mission 760, Dec. 24th 1944

Appendix 9: B-24 Malmedy Dec.24,1944

Appendix 10: GEE Navigation.

Appendix 11: GEE AMES 7000

Appendix 12: GEE Chart.

Appendix 13: 322d Bomber Group ( B-26, Malmedy, Dec.23d, 1944)

Appendix 14: 458th Bomber Group ( B-24, Malmedy, Dec. 24th, 1944)

Appendix 15: 387th Bomber Group (B-26, Malmedy, Dec, 25th, 1944)

Appendix 16: Bomb Group Combat Formation.

SUMMARY.

MALMEDY was erroneously bombed on 23 and 25 December, not the 24th, by the

IXth Bombardment Division (M), according to Ninth and Eighth Air Forces' records.

Photographs revealed the location, not pilot observation.

Personnel mis-identification was responsible.

Acknowledgement was made by the IXth BD in its daily report, but not by the Ninth AF.

During the Allied Air Commanders'Conference on 4 January 1945, General Carl Spaatz referred to an Alleged MALMEDY mis-bombing by the Eighth AF in December.

That reference was the source for the only allusion to the MALMEDY accidents by the Air Force's official history.

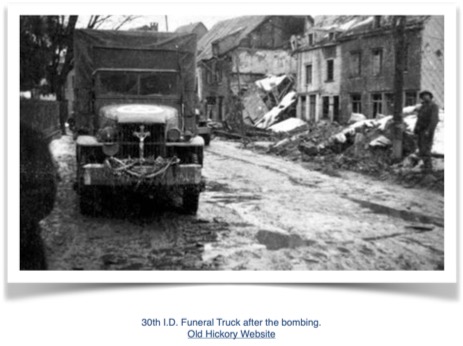

ZULPICH was the assigned primary of the 322d Bombardment Group for the 23d, but of the 28 dispatched B-26’s, six dropped 86 x 250 General Purpose bombs upon MALMEDY about 1526.

Their personnel realised ZULPICH was not bombed, but believed LOMMERSUM six miles beyond had been attacked.

Photographs disclosed MALMEDY was the victim.

The flight was off course, bombed some 33 miles short, a town in hilly, forested country, whereas ZULPICH was in the open.

Visibility was unlimited.

Enemy aircraft did not oppose, nor did flak prevent full load drops.

Four B-26's from the 387th BG dropped 64 x 250 GP's upon MALMEDY about 1600 on the 25th, instead of the nearby ST. VITH, the Group's objective.

Pilot interrogation indicated a mistake, and BORN was believed to have been the locality. Photographic interpretation by the IXth BD again pointed to MALMEDY as the location.

Personnel error was the apparent cause. Flight officers believed ST. VITH to be their position, inasmuch as instruments and visual observation agreed.

Plans-to-ground visibility was three to four miles.

23 DECEMBER.

Orders.

ZULPICH (F-230327) was the primary target

---no secondary, for the afternoon mission of the 322d BG.(VI, Bibl. #5, V)

It was a necessary railhead for the German Seventh Army, according to the IXth BP, which named the town as the 322d BG's target.

Bombing could be visual, if conditions permitted.

In turn, the 99th Bombardment Wing added that the route was to be from the base to K-7746, to the target, and bombing as to be blind from approximately 12,000 feet at 1500.

At 1145, the 322d's Operations notified A-2, and pilot were briefed et 1230-1330.

The Flight end Reports

Six B-26's attacked MALMEDY at 1526, while 22 others also dispatched to ZULPICH were aborted or bombed elsewhere.(I,IV,XI)

Maj. J. Watson's flight took off at 1328-1408.

According to the course map, the briefed route was flown, which was from the base to ROTGEN (InitiaI Point), to target, left to SIERVENICH, and return.

Pilots named LOMMERSUM (F-3445), some six miles northeast of ZULPICH, as the target of their 86 x 250 GP bomb. (IV,V) Their A-2 statements immediately after the 1655-1730 landing were descriptive.

Flight Leader, Maj. C. J. Watson. "hit town-not target-might be Lommersum. Excellent results on town."

2d Lt. D. R.Gustafson. --- "Center of town and walked out. Not target. Ex.”

1st It. S. E. Eyberg. --- "Hit town of Lommersum - not target. Excellent on town."

1st Lt. R. Pike. ---"Bombs through center of town - not target. Excellent results."

1st Lt. E. S. Isaac's. "Hit center of town - Was rot target. Excellent results on town."

Conley. "Bombs blanketed small town. Did not bomb primary. --- 3 or 4 runs on T/0.”

Based upon pilot reports, the Group telephoned the IXth BD about 1845 that ZULPICH had not been bombed, and believed LOMMERSUM had been attacked.(III,V) A 2210 amendment to the official OPFLASH #228 of 1915, repeated that data.

Photographs Identified MALMEDY

Flight cameras operated “100%," and Capt. Bernhard 0. Hougen, IXth BD Photo Interpreter reported:

"6 A/C. P.N.B. Bombs hit through the center of the town of Malmedy, on buildings and streets in the town."

His "center of town" description was identical with pilots'. (II, IV)

Although the IXth BD acknowledged the mistake, the Ninth AF did not.(I, Bibl. #5)

The IXth’s daily Mission Summary as to the 322d BG reported “... 6 a/c bombed the town of Malmedy, 1/2 mile of bomb line, due to mis-identification of target..." by bombardier.

In turn, the Ninth AF's Summary of Operations for the 23d, d4ted the 26th, referred only to EUSKIRCHEN and GLADBACH attacks by the 322d BG.

Pilot statements based upon impressions were the original 322d BG information, then when later photographic interpretation provided accurate details, the Group's December history related this version.(IXth)

"The Group's bombers headed for the defended area of Zulpich in the afternoon but weather conditions interfered with the operation and the majority of the aircraft brought air bombs back to base. Six aircraft misidentified the target and bombed the village of Malmedy in Belgium while four others bombed east of the village. ... Because of the fluid situation of the troop Lines during the German counter-offensive no serious damage to our troops was reported in the bombing of Malmedy."

MISTAKE EXPLANATIONS

Pilots were lost and committed a personnel error, yet several mission factors seemed to favour the flight.

Location.

MALMEDY was 33 air miles from ZULPICH, a substantial distance, even for aircraft, and LOMMERSUM was yet another six miles beyond ZULPICH.(X).

Actually, the flnight was off course and did not approach ZULPICH.(XI)

MALMEDY was on route to both base-to-target and base-to-IP of ROTGEN where the formation was to take positions.

Terrain Could Be a Guide.

MALMEDY was in hilly, forested country, ZULPICH in the open.(X) LOMMERSUM and MALMEDY were both on rivers, however, possibly a perplexity.

The former was on the ERFT, MALMEDY at the junction of LA WARCHE and LA WARChENNE RAU.(X)

Weather was Favorable.

Pilots reported CEILING AND VISIBILITY UNLIMITED.(IV) Their descriptions of results and photographs were both detailed, suggesting sharp observation.(IV,II)

Weather did not affect bombing, the IXth BD Weather Office reported.(VIII)

Enemy Was Not Distracting.

Aircraft opposition was lacking, and flak did not prevent dropping of 86 of the 87 carried bombs.(IV)

Attention Is called to possible tactical significance in the IXth BD's flak analysis of the 322d BG ZULPICH mission.(1)

The location's identity was uncertain, however, inasmuch as ZULPICH was the target, MALMEDY war bombed, but pilots believed LOMMERSUM had been attacked.

24 DECEMBER.

No MALMEDY bombing evidence was found among air force records.

Such an incident was not mentioned in the IXth BD's Mission

Summary, as on the 23d and 25th.(T) Descriptions of mission to the nearby ZULPICH and NIDEGGEN did not refer to formatting striking MALMEDY by mistake. Records were not examined of the 387th, 397th, 410th, 416th BG’s, which also attacked those two communication centres, inasmuch as they were unsuspected.

Some Eighth AF. heavy bomber attacks were made within the tactical area, but MALMEDY was not among them, according to the day's mission report No. 760 (2)

BIBLIOGRAPHY.

1. IXst Bombardment Division, Mission Summary, 24 Dec. 44. In Maxwell Field, Alabama. Air University. Air Historical Archives. 534.333, Dec. 44. Mission Summaries, Dec. 44.

2. Eighth Air Force, Mission No. 760. German A/F’s & Communication Center, 24 Dec. 44. ,IPIbid. 520.332 (or AF-8-SU-OP-S, 24 Dec. 44)

25 DECEMBER.

Flight and Reports.

Erroneous MALMEDY bombing by four 387th. BG aircraft occurred during the executed afternoon mission of the IXth BD against ST. VITH (VII, VI)

The 387th and 323d BG's dropped approximately 362-533 of 250 GP bombs, plus some 100's, enveloping the town in smoke. Briefing by the 387th BG was et 1300, and 36 B-26'n were dispatched at 1430, to fly a course southeastward from an undesignated point, below SPA and STAVELOT and ST.VITH. Actually the flight passed between STAVELOT and MALMEDY, bombed about 1600, then turned right at ST. VITH for the return.

This was Flight A, Box I, led by Pilot Anderson and Bombardier Shannon, followed by Pilots Missimer, Patterson, and Mueller.

The 387th BG realized at once that a mis-bombing had been place, but believed BORN (P-85040) to be the locality, a view repeated by the IXth BD in its first report.(II,V,VIII)

This town was mentioned in the Group's interrogation report, which was likely made within two hours of the landing. The more official OPFLASH to tie IXth BD carried the same information. In turn, the IXth BD' 15 Minute Mission Report noted in the 'deviation from route' column that “...850940 bombed by 1 flight" of the 387th BG.

Thus, based upon pilot observation, early reports pointed to BORN as the victim.

Photographs revealed it to be MALMEDY, which was acknowledged immediately by the IXth BD.(III)

Camera of the 387th BG operated "100%," and 1st Lt. Ben Mann, IXth BD Photo interpretation Officer reported:

Box I, Flight A did not bomb the primary. "Apparent misidentification of target as primary completely enveloped by smoke. Hits in town of MALMEDY approx. 10-3/4 mi. N.W.. of primary."

Official confirmation was made by the IXth BD's Mission Summary for the 25th, dated the 26th.(VII)

Referring to the 387th BG:

"The leader or one flight misidentified primary. This a/c plus 3 others dropped 64 x 250 GP at MALMEDY friendly territory. Bombardier and navigator believed they were synchronised on primary. ‘Gee' operator. obtained fix 3 minutes from BRP which corresponded with visual observation. Snow cover and haze made Pinpoint navigator difficult."

The section 'Failures to Bomb’ classified personnel as responsible, the reason: "Leader misidentified primary, dropping at MALMEDY -friendly territory."

The only other details were provided in 'Unsatisfactory Bombing Report', as instance probably by the IXth BD.(IV)

“Bombed on misidentified target. Bombed town of MALMEDY, 12 miles NNW of St. VITH. Bombardier and Navigator were both positive they were on briefed target. 'Gee' box was not working well but operator obtained supposedly accurate fix or course 3 minutes from BRP. This fix corresponded exactly with. bombardier's visual observation and no doubt existed as to his correct position. Snow cover and haze made pin point navigation difficult. All details concerning error not yet coordinated."

Mis-identification Reasons.

Personnel error was the apparent cause. Flight offices believed ST. VITH to be their position, inasmuch as navigation and2 visual observation agreed.

Weather seemed to favour the latter. Plane to ground visibility was three to four miles. (VII) Detailed photography was obtained, sufficient to identify the victim.(III)

ALLIED AIR COMMANDER’ CONFERENCE.

This was held at SHAEF in Versailles, Thursday, 4 January 1945.( General Carl Spaatz, U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe, reported:

“Eighth Air Force has operated…Towns in the battle area had also been attacked, including (so it was said) MALMEDY which was on our side of the line. “

General Spaatz was reporting presumably about the period since the last conference on 28 December.

That conference report was the cited source of information for the following statement in the Air Force history: (2)

One such town, Malmedy, was the scene of a tragic error, for it was held by Allied troops at the time it was bombed.”

The reference was the heavy bombers of the Eighth Air Force, but no date was mentioned, on an allusion to December operations of Ardennes.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.

1. Notes on the Allied Air Command’ Conferences, 4 January 1945. In Files of the Air Historical Archives, Air University, Maxwell Field, Alabama.

2. The Army Air Forces in World War II. Vol. Three, EUROPE:

Argument to V-E Day, January 1944 to day 1945. Chop. 18, Autumn Assault on Germany, by John E. Fagg. p. 670. ln Army Library; General Reference Section, OCMH; Air Force Historical Office.

DOCUMENTATION.

23 DECEMBER 1944. (Malmedy bombing)

By 322d Bombardment Group(M), 99th Combat Bombardment Wing, 9th Bombardment Division(M).

I. 99th BD(M) Mission Summary ( afternoon) 23 Dec. 44. Dated 24 Dec. 44. (Bibli. #1)

“Zulpich (Communication Center)

322 BG: 28 a/c dispatched (including 2 PFF a/c). 5 a/c bombed other targets, dropping

64 x 250 GP- 3 window a/c.

18 a/c failed to bomb: 6 a/c flight leader could not locate target due to weather.

2 PFF a./c returned to base after navigator determined that formation would be 12 minutes late at target due to late takeoff. 6 a/c bombed the town of Malmedy, 1/2 mile w of bomb-line, due to misidentification of target. XXX 4 a/c other reasons:

2 a/c jettisoned bomb. wEen a/c were hit by flak. 1 a/c could not catch formation.

1 a/c did not drop as leader jettisoned. Bombs of 1 a/c witch landed Couvron unaccounted for.

4 a/c attacked casual target, the location and type unknown at this time.

No photo coverage or visual observation.

1 a/c attacked the town of Goldbach (F-230410). No photo coverage or visual observations of results.

No losses, 18 a/c flak battle damaged, no casualties ."

FAILURES TO BOMB

Group | No. A/C | Classifications | Reason |

322 | 1 | Personnel | Bombardier misidentified target |

5 | Other | Bombs hit town of Malmedy in friendly territory |

OBSERVATIONS

WEATHER: Zulpich 322 BG: Clear, Snow on Ground, Visibility 4-6 miles in haze

Photos Reports.

No photos available.

322d’s cameras photographing 100%

Flak AnAnalysis Annex.

Zulpich Rail Communications Center. 322 BG.

No A/C were lost to flak, but 18 were damaged.

"Flak in the target area started out to be moderate and inaccurate. However, as the /C reacted the Inner defence zone of 18 km heavy guns, the fire became intense and accurate. This target represents one of the more heavily defended areas of the enemy's communication system. Moderate to intense fire could be expected from the 18 heavy guns plotted."

II. BD Photo interpretation.

S-2 Report( First Phase Interpretation), signed (typed name) by Capt. Bernhard 0. (Hougen), Photo Interpreter.

Target hit: Malmedy.

A. Target Briefed; Zulpich- - -Primary.

None --Secondary.

M.P.I.: Center of Town.

A.P. .Same.

C. No. & Type of A/C dispatched: 26 B-26e. 11 attacking.

D. No. and size of bombe dropped:

4 x 1000 GP

150 x 250 GP

F. Heading A/C when bombs drooped: Approx. 30'

G. Time bombs dropped: 1526.

H. Activity at target: None.

J. Results of bombing:

"Due to operational difficulties, weather, and enemy activity the A/C could not fly their designated positions in their respective boxes and flights; it is impossible to determine the bombing by either boxes or flight due to this.

#6 A/C. P.N.B. Bombs hit through the center of the town of Malmedy, on buildings and streets in the town.

#1 A/C. P.N.B. Location of strikes undetermined due to poor quality of photos, hits in fields, A/C hit by Flak, one engine out, jettisoned bombs.

No photos of otter bombings."

N.B. --- PNB was probably Primary not Bombed, according to postwar AF sources.

III . 322 BG’s OPFLASH REPORT

To be teletyped to the IXth BD within two hours after last plane landed.

B. Briefed Primary: ZULPICH

D. No. A/A Attacking:

Primary. _

6 Secondary. “Believed Lommersum F3435 -- hit center of town -- Excellent."

F. Bombs.

86 Secondary.

G. Results of BombIng on:

Primary

Secondary. "Believed Lommersum - Fit center of town and walked through. Excellent."

H. No. A/C: (As to casualties)

5 damaged.

J. Flak: Target: Mod & Inac.

Elsewhere: IP Intense ard Acc.

L. Altitudes of Attacks: 12,000 Secondary.

M. Time over Targets 1526-1530, Secondary.

The more official OPFLASH from the 222 322 Group was the teletyped OPFLASH No. 228 for 23 Dec. at 231915A Dec., to the IXth Bomber Command (A?t: A-2) and CG, 99th Combat Wing.

was amended at 2210A, to indicated some of the above data. The most important was Par. D to read; 11 A/C - Secondary-Lommersum (F3435).

#4. 23 Dec.

IV PILOT INTERROGATION REPORTS

WATSON (Maj. G.J.); Eft Ldr; Box 1, Flt. 1, Pos. 1; took off, 1408, landed, 1655.

Altitude, 12,300; hour, 1526.

"Hit town - not target - millet be Lommersum. Excellent results on town."

Bombs: Dropped load of 13 x 250 GPs.

Weather: Ground haze. CAVU.

Flak: Intense and accurate.

Opposition: none.

GUSTAFSON (2d Lt. D.R.); 451 Sq.; Box 2, FIt. 2, Pos. 4; took off, 1340, Landed 1700.

Alt., 12,000; 1529.

Center of town and walked out. Not target. Ex."

Bombs: Dropped load of 16 x 250 GPs.

Weather: 0/10 in hase.

Flak: intense, accurate.

Opposition: None.

EYBERG(1st. Lt. S.E.); 452 Sq.; Box 1, Flt. 3, Pos. 1; took off, 1404, landed 1705.

Alt. 12,300; 1526 hrs.

"Hit town of Lommersum - not target. Excellent on town.

Bombs: Propped load of 26 x 250 GPs.

Weather: Ground haze. CAVU.

Flak: Intense, accurate at IP.

Opposition; None-..

PIKE (1st Lt. R.W.); 451 sq.; Box 2, Flt. 2, Pos. 1; took off 1328, Landed 1700

Alt. 12,000; 1530 Hrs.

“Bombs through center of town - Not target. Excellent results.”

Bombs Dropped load of 13 x 250 GPs

Weather Haze on ground. CAVU.

Flak: Intense and accurate.

Opposition: None.

ISAAC (1st Lt. I • S.); 450 sq.; Box 1, Flt. 2, Pos. 4; took off, 1408, landed 1720.

Alt 12,000; 1526 hrs.

“Hit center of town- Was not target. Excellent results on town."

Bombs Dropped 12 of 13 x 250 GPs.

Weather CAVU.

Flak: Intense, Accurate.

Opposition: None.

CONLEY(?) ; 451 Sq.; Box 2, Fit 2, Pos. 2; took off, 1335, landed 1730.

Alt. 12,000; 1530 hrs.

"Bombs blanketed small town, did not bomb primary. -- 3 or 4 runs on T/0”

Bombs Dropped load of 16 x 250 GPs; "Salvoed bomb: around."

Weather: Over secondary, ground-haze 2/10 strato.

Flak: Primary target, intense, accurate.

Oppositions 2 ME 109a SE Zulpich.

V. 322d BG’s A-2 Log of Mission, 23 Dec. 44. (Bibi. #1)

ZULPICH Defended Area.

1145 - Notified of target by operations.

1230-1300 Pre-briefing.

1520- F/O #399 and Intelligence annex recv’d.

1640 Interrogation started.

1730 Interrogation ended.

1845 - OPFLASH and 2-hour phone report.

VI. Orders.

- IXth Bombardment Division (V)

(Bibl. #4)

1. Typed summary of FO #680.

The 322d BG of the 99th B was to bomb, blind, the Zulpich Railhead, F-230327, at 1530.

2. A chart (typed) of the wing's missions and detailed

The 99thh B Wing's: target was the Zulpich Railhead, F-230327. The notation "Spec. Photos" was entered in the target column, probably indicating the requirement to take them or the target had been set up as the result of such photos.

Specifically, the target was a small railhead 7 miles from the bomb line, and in general, Zulpich was to be bombed as a mall village with important road net.

Attack's objective was to destroy supplies in the railhead and to cut communications in the area.

A TACTICAL SIGNIFICANCE column applied to railheads of MUNSTEREIFEL, ZULPICH, NIDEGGEN, as follows

*The German 7th Army which jumped off in an attack about 6 days ago are depending on these 3 feeder line railheads for all types of supplies and reinforcement, as the Germans expected to capture a great deal of supplies and as they did not, they are rather in bad need of supplies."

Bombing Visual and Blind.

N.B.—Bomb-line mentioned was that of the Medium Bomber interdiction line which curved westward from the RHINE near BONN to pass midway between ZUPICH and DUREN.

(Bibl. #5, p. 691.)

B. 99th B Wing’s FO #399, 231430 Dec. 44, and intelligence Annex at 231441 Dec.

(Bibl. #1)

ZULPICH (F-230237) was specified as the target, with zero hour to be 231500 for Plan B(Blind.), and bombing at 12,500 and 12,000 feet. The route was to be from base to K-7746 to Target, thus was well north of MALMEDY.

VII. Maps.

B.S.G.S (?). 4042: North West Europe, 1:250,000. Sheet 3, Brussels-Liege.

B.S.G.S (?). 4042: North West Europe, 1:250,000. Sheet 6, Namur-Luxembourg.

B.S.G.S (?). 4346; Central Europe, 1:250,000. Sheet K 51, Koln.

B.S.G.S (?). 4416; 1:100,000. Sheet ? , Bonn.

VIII. WeatherOffice IX’s BD.

(Bibl. #4.)

Its Flash Report, dated 23 December, for the 322d BG was the following:

?22ND Bomb Group

Target: F-23027 (1530) ZULPICH

Target: Clear, Snow on Ground. VSBY 4-6 Miles in Haze.

Did Weather Effect Bombing: No.

IX. 322d FIG's history, December 1944. Undated. (Bibl. #2)

"The Group's bombers headed for the defended area of Zulpich in the afternoon but weather conditions interfered with the operation and the majority of the aircraft brought their bombs beck to base. Six aircraft misidentified the target and bombed the village or Malmedy in Belgium while four others bombed past of the village. Several others bombed casual targets. Because of the fluid situation of the troop lines during the German counter-offensive no serious damage to our troops was report'd in the bombing of Malmedy. Eighteen aircraft were flak damaged but there were no losses or casualties.

X. Malmedy-Zulpich Distance and Terrain.

Examination of a 1:100,000 map (see VII above) indicates the air distance to have been approximately 33 miles. MALMEDY was situated at the junction of LA WARCHE RIVER and LA WARCHENNE RAU, the terrain being hilly and forested. ZULPICH and nearby (northeastward) LOMMERSUM were in open country, the latter also on a river, the ERFT.

XI. Route: 322nd Bomb Group (V). 23rd Dec 1944

Target: Zulpich Deferred Aree. TOT: 1530-1532.

Alt: 12,200-11,500.Weather CAVU

Briefed Route

1st Box's Route

2nd Box's Route

Source: GP-322-SU-OP-S, 23 Dec.44. Zulpich Defined Area.

534.332A. 23 Dec. 44. 9th BD. F.O's 680. 23 Dec. 44

XII. Bibliography.

Maxwell. --- Documents were obtained through the Air Historical Liaison Office in Washington, from Maxwell Field, Alabama. Air University. Air Historical Archives.

- 322d Bombardment Group, Supporting Documents. GP-322-SU-OP-S, 23 Dec 44. Zulpich Defended /res. In Maxwell.

- 322d BG, History. GP-322-Bi. Dec. 1944. (Bomb-) In Maxwell.

- IXth Bombardment Division (M), Daily Mission Summaries, December 1944. 534.333. In Maxwell.

- IXth BD, Field Order #680. 23 Dec. 44. 534.332A, 23 Dec. 44. In Maxwell.

- Ninth Air Force, Mission Files, 23 Dec. 1.4. 533.334. In Maxwell.

25 DECEMBER 1944.

By 387th Bombardment Group, 98th Bombardment Wing, IXth Bombardment Division(M), Ninth Air Force.

I.Formation for 25 Dec. 44, 387th BG. (Bibl. #2)

Green Flight: Records did not identity the following as to rank and given names:

Lead A/C-- Pilot Anderson, Bombardier Shannon, in A/C #684.

Other A/C--- Pilots Mueller, Missimer it #880,#700; and

probably Patterson in #717, instead of Moffett of #899.

Briefing at 1300; Takeoff at 1432.

II. Interrogation Form of 387th BG, 25 Dec. (Bibl. #2)

The flight lead by Anderson appeared to have been composed of Anderson, Mueller, Missimer, Patterson.

Tookoff it 1432; Target was St. Vith; Date 25 Dec.

Flight dropped 64 x 250 on the target. BORN was noted as locality.

III. IXth BD, Photo Interpretation (First Phase Inter.) (Bibl. #2)

Report by 1st Lt. Ben Mann, Photo Interpretation Officer, of 398th BG (98th BWg) operations of 25 Dec.

Target briefed and hit ---St.Vith. A/C attacking--30.

Drop at 1605. Activity at target: "Target area completely enveloped by smoke, making identification of target on their heading extremely difficult.

Results of bombing: Box I, Flight A. Anderson-Shannon.

PNB (Primary hot Bombed). "Apparent misidentification of target as primary was completely enveloped by smoke. Hits in town or Malmedy approx. 10-3/4 mi. N.W. of primary.”

Flights B and C or Box I attacked St.Vith.

Box II, not involved in Malmedy. Flight A, Morse-Britton bombed Rocherath by mistake, instead of St.Vith, and that incident was that referred to in the History (December) of the 387th BG.(Bibl.#1)

IV. "Unsatisfactory Bombing Report.,0 (Bibl. #2)

For 387th BG, Mission of 25 Dec. 44 to St.VITH Issuing organisation was rot Identified, but it was likely the BD Unsigned; undated.

Box I, Flight A, Pilot Anderson, Bombardier Shannon-

Visual Bombing. Results: PNB.

“Reasons for ? Bombing or Failure to Attack Primary:

Bombardier misidentified target.

Bombed town of MALMEDY, 12 miles NNW of ST.VITH.

Bombardier and Navigator were both positive they were on briefed target.

'Gee' box were not working well but operator obtained supposedly accurate fix on course 3 minutes from BRP. This fix corresponded exactly with bombardier's visual observation and no doubt existed as to his correct position. Snow cover and haze made pin point navigation difficult. All details concerning error not yet coordinated.”

V. Group's OPFLASH, 25 Dec. (Bib1.12)

No mention of Malmedy mistake. Report would give impression the primary had been bombed as briefed, with certain exception.

One flight of 4 a/c may have bombed BORN P-850940.

VI. Overlay of Mission, by 387th BG. (Bibl.#3)

TOT, 1600; Altitude 12,500; Weather Nil clouds,Vis. 5 mi.

Briefed Route

VII. IXth BD, Mission Summary (Afternoon), 25 Dec. 44. Dated 26 Dec. 44, as to Field Order ff683 (Bibl.#3, #4)

“ST. VITH (Defended village)

387th BG: 36 a/c dispatched, 26 dropping 426 x 250 GP on and in vicinity of primary. ...

…

The leader of one flight misidentified Primary. This a/c plus 3 other dropped 64 x 250 GP at Malmedy - friendly territory. Bombardier and navigator believed they were synchronised on primary.

'Gee' operator obtained fix 3 minutes from BRP corresponded with visual observation. Snow cover and haze made pinpoint navigation difficult.

…

Box I - Bligh . A. P.M.B. Apparent misidentification of target as primary was completely enveloped by smoke. Hits in town of Malmedy approximately 10 3/4 miles NW of primary.

…

Other ST. VITH Attacks.

323d BG dropped from 40 a/c, 533 x250, 168 x100 ???

394th PG dispatched 39 a/c, but none bombed.

VIII- IXth MISSION REPORT

Failures to Bomb.

GP A/C Classification Reason.

387th 1/C Personnel "Leader misidentified primary, drooping at Malmedy

- friendly territory.'

S/A Photo Reports

387th cameras operating 100%

WEATHER: No clouds. Visibility 3-4 miles plane to ground.

VIII. IXth BD. Mission Report (15 Minute Report' (

(B bl. #3)

387th BG: 36 A/C; TOT 1500; Bombed primary; Deviation from route, etc.

--- *850940 bombed by 1 flight.”

IX. Eighth Air Force. (Bibl. #5)

No indication found among records.

Notes:

- More than 10,500 bombers of the U.S. Eighth Air Force were lost during the war.

- Statistically, a crew member had only a 25 percent chance of surviving 25 missions

X. Bibliography

Maxwell.: Documents were obtained though Air Historical Liaison Office in Washington, from Maxwell Field, Alabama. Air University. Air Historical Archives.

1. 387th Bombardment Group, History. GP-387-Hi Dec. 44. In Maxwell.

2. 387th BG, Supporting Documents. GP-387-SU-OP-S(b), 25 Dec. 44. In Maxwell.

3. IXth Bombardment Division (M), Field Order #683, 26 Dec. 44. 534.332 FO #683, 25 Dec. 44. In Maxwell.

4. Ninth- Air Force, Mission Summary, 25 Dec. 44. 533.334. Mission File, 25 Dec. 44. In Maxwell.

5. Eighth- Air Force, Mission #761, 25 Dec. 44. 520.332.8’th AF Might FO 1451A and Mission No. #761. 25 Dec. 44. In Maxwell.

WIKIPEDIA

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/387th_Air_Expeditionary_Group

APPENDIX 1 387th BG:

(https://387bg.com/387th%20Bombardment%20Group%20-%20Chronology.htm)

1 Dec 1942 – Group and squadrons activated

The 387th Bombardment Group (M), with its four member squadrons, the 556th, 557th, 558th and 559th, was activated at MacDill Field, Tampa, Florida December 1, 1942.

– History of the 387th Bombardment Group (M) AAF, p. 4.

…

Sat, 23 Dec 44 – Mission: Prum defended area

In Germany, around 500 B-26s and A-20s attack rail bridges, communications targets, villages, a rail junction and targets of opportunity losing 31 bombers; fighters fly bomber escort,...

– Jack McKillop, Combat Chronology of the U.S. Army Air Forces.

Meanwhile the planes, after being grounded for several days by heavy fog, took off on December 23 to get the Mayen railroad bridge, an important link in the enemy’s supply system. Ordered to bomb by PFF, the crews found CAVU conditions in the target area and scored, as was learned later, four excellent and one superior out of seven flights. Just after crossing the bomb line en route to the target, the formation was jumped by fifteen to twenty-five ME-109s, who concentrated on the low flight of the second box and knocked down four ships—those of Lieutenant W. O. Pile, W. N. Church, C. O. Staub and W. J. Pucateri.

Partial compensation for this loss was the destruction of four ME-109s and four damaged by Technical Sergeant Joseph Delia, Staff Sergeant D. D. Fasey and Sergeants James Jones, Ed Wesolowski and Leo Mossman. The other flights, after the Germans had been beaten off, continued to the target through intense and accurate heavy flak and destroyed the bridge. The fifth plane was lost when Lieutenant Smith’s plane was picked off just before “bombs away.” In returning to the field Lieutenants W. P. Wade and T. G. Blackwell were forced to crash-land their badly damaged ships.

– History of the 387th Bombardment Group (M) AAF, p. xxx.

Just preceding Christmas Lieutenant Don Whitsett had flown his seventy-fifth mission in”Mississippi Mudcar” and had departed for the States. This plane was one of the original B-26s which had been ferried across the north Atlantic in June 1943; Lieutenant Whitsitt had flown in it as co-pilot. On December 23rd the “Cat” was shot down on its 150th mission.

– History of the 387th Bombardment Group (M) AAF, p. xxx.

Finally, on December 23rd, the weather over the Bulge area cleared and fighters and bombers from both the 8th and 9th Air Forces literally swarmed over the battlefield. The Luftwaffe was also out in a surprising show of strength.

The initial target of the 387th was the railroad bridge at Mayen, Germany, approximately 25 miles west of Koblentz, which carried a critical rail line to the battlefield. Our losses for the mission were seven of the thirty-six aircraft which were launched. The target for the afternoon mission was Prum, a communications center approximately 35 miles east of Bastogne.

...

On the 23rd of Dec., 1944, the first day that we could launch a mission in the Battle of the Bulge, I flew as a substitute co-pilot on both the Mayen and Prum missions. During the former, our a/c was in one of the wing positions in the first box and except for the excitement of finally being able to join in this critical battle, it was a fairly routine mission from my standpoint.

When we reached our fighter rendezvous the escorting fighters failed to appear and, as briefed, the leader turned on course over Bastogne.

We didn't realize it at the time, but for some reason our second box missed the turn and became separated from us by five or six miles. In addition, their low flight was lagging behind the box leader. This violation of formation discipline resulted in a flight of ME 109's effectively attacking the low flight and shooting down four of the six a/c.

In the first box, although we were aware of enemy fighter activity by the radio chatter, no enemy aircraft were in view from the cockpit. Flights in the first box approached the target in a routine manner, went into their in-trail formation and scored excellent results on the bridge. The flak was accurate and heavy, but no a/c were lost over the target.

In the meantime, the second box was engaged in a running gun battle with the ME 109's until one minute prior to opening their bomb bay doors. The two surviving Marauders from the low flight had tacked on to the lead flight. The Box Leader, realizing he was approaching the target on a heading different that that which had been briefed, made a 360° turn and lined up properly for the bomb run. The high flight followed him and the two flights made long steady runs and dropped with excellent results.

Both boxes sustained further flak damage on the way out, losing another aircraft and two aircraft crash landed at the base. Photos showed one span of the bridge destroyed and another span partially destroyed.

Within a few minutes after climbing out of the a/c, I was in a truck going to the briefing tent in preparation for a mission over Prum, Germany, a communications center for the German ground forces attacking in Belgium. As a substitute co-pilot for one of our Flight Commanders, I had more battle-time to observe the intense aerial activity over the area of the battle.

Our group was at 10,000 to 15,000 feet—the B-17's and B-24's were above us, probably at 20,000 to 25,000 feet and flights of P-47's could be observed peeling off below us in dive bombing and strafing attacks.

Prum was about thirty five miles northeast of Bastogne and I recall the flak was especially accurate as we flew toward the target. Regardless of our evasive action, the bursts seemed to be all over us. As our flights manoeuvred into their in-trail formation to commence the bomb run, the flight of six ships ahead of us from another group, literally blew apart. I presume the lead ship received a direct hit and the other five aircraft banked away to his right and left.

The 387th had been able to launch only 26 aircraft for this mission instead of the customary 36, and 21 of the 26 received battle damage. The bombing results were excellent.

– Paul Priday (556th B.S.), Mission to Mayen.

The 387th Group lost four bombers and a pathfinder to some 20 German fighters that blasted away at the B-26s between Bastogne and their target at Daun... In the hit on Mayen, the 387th suffered the loss of four Marauders to enemy fighters and another two to flak after failing to find their escort from the 367th Fighter Group. The B-26s did, however, claim 4 German fighters downed.

– Daniel Parker, To Win the Winter Sky, pp. 234.

The 387th and 394th BGs hit the village of Prüm east of St. Vith. The 387th lost only one plane due to flak damage. The crippled bomber was hit just before the bomb run and suddenly arched over on its back. The pilot somehow managed to roll over and straighten out in time to drop its bombs before the B-26 fell off to the side and spun to the ground...

– Daniel Parker, To Win the Winter Sky, pp. 235-236.

Staffeln of JG 11 opposed the 70 B-26 Marauders of the 387th and 394th BGs bearing down on the marshalling yards at Mayen.

– Daniel Parker, To Win the Winter Sky, pp. 243.

Sun, 24 Dec 44 – Mission: Nideggen railroad siding

276 B-26s and A-20s hit rail bridges and communications centers in W Germany; fighters escort the 9th Bombardment Division,...

– Jack McKillop, Combat Chronology of the U.S. Army Air Forces.

Mon, 25 Dec 1944 – Mission: St. Vith road

Nearly 650 B-26, A-20s and A-26s hit rail and road bridges, communications centers and targets of opportunity in W Germany and the breakthrough area;...

– Jack McKillop, Combat Chronology of the U.S. Army Air Forces.

Following the attacks on Prum and Nideggen the Group, on Christmas day, a mid hail and snow, went after the Irrel road junction. On this mission occurred one of the most heroic incidents in the history of the Group.

The lead plane of Lieutenant John A. Alexander of the low flight was hit hard by flak over Bastogne, four minutes from the target. Two minutes later the interphone was shot out and a few minutes after the intervalometer. Since the time remaining was too short to make the necessary adjustments, Lieutenant Harvey W. Allen, the bombardier, signalled to the pilot to make another bomb run. With rudder, ailerons and wings full of holes, Lieutenant Alexander managed to hold the plane level so that the bombs could be salvoed, hitting inside the target area.

Losing altitude fast and perceiving an indicated air speed of only 160 mph, Lieutenant Alexander coaxed his ship back across the bomb line near Trier and ordered the crew to bail out. Seven of the nine aboard made the jump, but staff Sergeant Michael Aguilar was thrown against the radio table and his chute flew open.

Lieutenant Alexander gallantly offered to try to crash land the plane, but Sergeant Aguilar gallantly refused to agree, realizing the impossibility of a crash-landing among the hills. Climbing gingerly down through the nose wheel with the parachute draped over his arm, Sergeant Aguilar successfully made the jump.

At 700 feet Lieutenant Alexander bailed out and watched his plane crash into a small creek and explode. They were not yet out of danger, for some American soldiers, thinking they might be Germans, fired at them before they could identify themselves. For their acts of gallantry, Lieutenant Alexander was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal and Lieutenant Allen and Sergeant Aguilar the Silver Star.

In the afternoon a 387th formation attacked St. Vith with excellent results, but the most exciting events of the day were to happen after the mission.

A 397th plane, coming in after dark, hit short of the runway, burned and exploded. The twenty-eight 100 pound demolition bombs knocked out nearly all windows, both on the base and in Clasteres. Fortunately all the crew escaped. About twenty minutes later a 387th plane, returning with sixteen 250’s from a test flight, came in. In landing the nose wheel tire was punctured by a bomb fragment from the 397th ship, the 387th plane nosed over, caught fire and exploded. This crew also escaped, but all other whole window panes in Group headquarters were shattered.

– History of the 387th Bombardment Group (M) AAF, pp. xxx.

Came a never-to-be forgotten Christmas Day. In the morning the target was a road junction at Irrel. Ground in the target area was blanketed with freshly fallen snow, and have made bombing more difficult. Nevertheless, most of the formation hit the target for good results, and the rest bombed the defended town of Echternach; also with good results. Making a secondary run on the primary target, the ship of Lieutenant [John] Alexander, leading the Low Flight of the II-Box, was hit hard by Flak, knocking out his one engine and the bombsight. Lt. [Harvey] Allen, bombardier, ingeniously got his bombs away in the target area, nonetheless, allowing his flight to bomb.

In turning off the target, the ship was hit again and again by Flak; the rudder being badly damaged, both left gasoline tanks punctured, the top turret smashed and the nose Plexiglas of the plane shattered.

Lt. Alexander kept the ship under control while Lt. Allen and Sgt. Miller, GEE Operator, directed him to friendly territory, where all nine men in the crew safely parachuted. S/Sgt. Aguilar jumped after his parachute had opened accidentally inside the aircraft, and Lt. Alexander, last man out, with difficulty jumped from the careening plane at 700 feet. The plane was seen to crash seconds later into the bank of a small stream. All of the men returned later. None of the remaining nine planes furnished by the squadron received damage.

– 556th Squadron, Monthly Report, December, 1944.

On the Group's morning mission to Irrel, Germany, 1st Lt. John A. Alexander-0699645, by his undaunted actions, earned our country's second highest honour for valour, the coveted Distinguished Service Cross.

– Peter Crouchman, Alan Crouchman, Robert C. Allen, William J. Thompson, Jr., 556th Bomb. Squadron, B-26 Marauder Reference and Operations Guide, p. 52.

1st Lt. James M. Neff was our crew's pilot, and I might add, a damn good one. His skills were certainly taxed to the limit during the afternoon mission to Saint Vith, Belgium on Christmas day.

After waiting most of the morning for a special mission, which did not materialise, our six plane flight was tacked on to the Group's second mission. The I.P. was the town of Malmedy, approximately twenty-eight miles north of St. Vith. The target was heavily defended, and the scene of much Allied aerial efforts to disrupt German traffic in the area. We had a fresh snowfall on Xmas morning, the first of that cold winter. The visibility over the target was excellent, and each flight bombed visually.

I was in my gun position as tail-gunner, as our flight levelled out for the bomb run. Lt. Vernon Briscoe was calling last second corrections., when our plane seemed to shudder. The next second, I saw the planes in our flight do what I thought was a climbing right turn. This brief recollection lasted only a millisecond before I realized our plane was descending fast in a steep left turn. I saw smoke coming from one of the engines and called Neff on the intercom. His calm reply was, "I know it." He called Gamble to come forward, "On the double." I then saw that the left wing had holes in it, as well as the tail section. Neff adroitly managed to control our descent, and told the crew to standby to bail out. I grabbed my chest pack and met Walt Simmons(AG-top turret gun.) at the waist gun window. Walt plugged into the waist window intercom as I made ready to jump.

I learned later... that when Gamble went forward, he waded through ankle deep gasoline in the aft bomb bay. He notified Neff of this potential danger. The pilot's compartment was a shambles. Jimmy Harris, our copilot, was bleeding from shoulder and face wounds, the plexiglas was shattered and the pilot's instruments were shot out. Neff had his hands full trying to maintain control of our aircraft's descent. Bris and Lt. Russ Trapper, our navigator, along with M/Sgt. Paris "Hoop" Hooper, our GEE operator, were feverishly, but methodically, plotting our position, and relaying headings for Neff to steer in order to be over friendly lines.

The left engine seized up and Neff feathered it, when Harris announced that our right engine had burst into flames. The danger was very great for a mid air explosion, and Neff and Gamble realized it. At the persistent coaxing of our calm bombardier, Neff delayed the bail out order until Bris assured him we were over our lines. Neff ordered Trapper and Briscoe out of their nose compartment, and then gave the order to bail out. Walt and I exited the flaming aircraft from the waist window, while the other six members used the open bomb bay. Neff was the last member of the crew to jump. The B-26G circled under him, and then exploded in mid air! The fuselage fell into the Muese River near Huy, Belgium, while its two engines fell on each embankment. Four of us descended by parachute into the front-line positions held by the 84th Inf. Div., where we ate our Xmas supper. Harris ended up in a Paris hospital, and the rest of us arrived back to the 387th BG within three days. I suffered injuries to my ankles, while Bris was crippled with a knee injury. Luckily, no one else was injured. On board were:

Pilot Copilot *Bomb. Nav. *GEE ROG EG AG | 1st Lt. 2nd Lt. 2nd Lt. 2nd Lt. M/Sgt. T/Sgt. S/Sgt. S/Sgt. | James M. Neff James I. Harris. Vernon L. Briscoe Russell H. Trapper Parris W. Hooper Wm. J. Thompson, Jr. Wm. F. Gamble Walter H. Simmons |

*Received DFC | ||

– Peter Crouchman, Alan Crouchman, Robert C. Allen, William J. Thompson, Jr., 556th Bomb. Squadron, B-26 Marauder Reference and Operations Guide, p. 61.

Lieutenant Harvey Allen, bombardier on Lt. lead crew, suffered facial lacerations when the B-26 Plexiglas nose was shattered during their initial bomb run over Irrel. Lt. Allen reported that his bombsight was also damaged by the flak. On their flight's second bomb run, Lt. Allen aligned the secondary target up visually and they were able to place all their bombs in the target area. For his actions, 2nd Lt. Harvey Allen was awarded the Purple Heart and the Silver Star.

Staff Sergeant Michael C. Aguilar's rip cord caught on the radioman desk in the confined compartment of their stricken plane. His parachute prematurely popped open as the crew were making their emergency exit from the Marauder. When Lt. Alexander saw Aguilar's plight, he offered to stay with their falling plane and attempt to make a crash landing in the mountainous terrain, in order to give his engineer a chance for survival. The airman realized the great risks of Lt. Alexander's offer. It was then that Anguilar (it is reported) picked up his unpacked parachute, draped it over his shoulder, and exited through the nose wheel. Fortunately, his parachute and shroud lines performed perfectly and he floated to earth safely. Lt. Alexander was right behind him. To add to their hectic experience, friendly infantrymen opened fire on them when they landed.

– FW Supplemental Section, Personal Experiences & Anecdotes By And Of The Men Of The 556th Bomb. Squadron, p. 52-A.

[This account reports that the flight was attacking the secondary target; this is probably incorrect.]

When the aircraft suffered its initial flak damage, Mike Aguilar, Engineer/Gunner, came forward from his position in the top turret to assist in the cockpit. As Mike passed through the bomb bay the ripcord of his chest pack parachute was snagged and the chute was accidentally opened. After "Bombs away," when it became apparent that the aircraft would have to be abandoned, John gave the order to bail out.

As John struggled to control the rapidly descending "June Bug," crew members exited the aircraft until only John and Mike remained. At that point they were faced with an agonizing decision. As aircraft commander, John was duty and morally bound to attempt a crash landing if Mike was unable to jump. If Mike elected to gather his opened chute in his arms and exit the aircraft, he faced the very real possibility that his chute would prematurely deploy and snag on some portion of the aircraft, carrying him to certain death. Another possibility was that the canopy would become twisted or entangled in the shroud lines and fail to properly deploy.

Considering the uneven terrain over which they were flying, an attempted crash landing was a questionable alternative. Mike decided that he would jump rather than risk both of their lives. Miraculously, Mike's parachute deployed and he landed safely. John exited the "June Bug" as soon as possible after Mike's departure and, though perilously close to the ground when his chute opened, survived the touch-down.

For his heroic act of unselfishness, Mike was awarded the Silver Star. So was Harvy Allen, Bombardier, who had gallantly effectively directed the successful bomb run after the nose section had been seriously damaged by flak.

On 25th of December 1944 the 387th was assigned to hit the target at St. Vith in the bulge. We misidentified the target and hit a small town a few miles away. That small town just happened to house the headquarters for the German General who commanded the German forces in the bulge. That general wrote an article that appeared in Life magazine in December of 1945 wherein he suggested that our mistake crippled the effectiveness of his headquarters. I hasten to add that the first two boxes of the 387th did hit St. Vith, but my box did a 360 degree turn at the I.P. to provide better separation, and lost sight of the first two boxes. I read the article in Life waiting to get a haircut. I would love to have someone find a copy of the article and make it available. Please e-mail me. Thank you.

Thomas C. Britton, Major, USAF (Ret'd) <britton@mcn.org>

– Wednesday, July 26, 2000 at 13:51:17 (CDT)

APPENDIX 2 387th BG:

https://387bg.com/387th%20Bombardment%20Group%20-%20Operations.htm

Most replacement aircraft were usually given names by the pilot--and his crew--that the plane was assigned to, but seldom were these names painted on the ship. This was always a mystery to me? Thinking back, I'm inclined to believe that the ground crew that maintained the aircraft had a big influence on whether the ship was adorned with the name chosen by the pilot, or one that they preferred.

By the time the 387th BG moved from its original overseas base at Chipping Onger, to its transitory base at Stoney Cross, the turnover in veteran air crews had begun. The close knit ties that had been woven between air and ground personnel, during the founding and training days of the squadron and Group, were being broken up by the influx of "the replacements."

For most of the ground personnel, whose skills were required until war's end, this transition was taken in stride. But, for others, it took much longer to accept the "new men." This was understandable. I do believe, however, that by VE-day even the most dubious veteran became convinced that "the replacements" were indeed "satisfactory."

The early B-26B's in the 387th BG were the original planes flown overseas by the cadre of the flight personnel. These planes were picked up at Selfridge Field, and for the most part, the ships were adorned with their new names at that time. Overseas, as the deadly business of air warfare progressed, getting the planes airborne, and on target, became top priority, regardless of who flew them.

– William J. Thompson, Jr., 556th Bomb. Squadron, B-26 Marauder Reference and Operations Guide, p. 67.

The aircrews hated the weather over England and the Continent. The first task that confronted everyone was that of insuring that the aircraft were free of frost and ice and that they stayed that way until take-off. Once airborne, there usually was an instrument climb through a heavy overcast to form up "on top.”. The climb, itself, was usually hazardous as the freezing level normally extended from close to the ground to well up into the clouds where heavy snow might be encountered. Adding to the dangers in the climb out, aircraft often overtook other aircraft of its own unit or encountered aircraft of other units descending.2 It was truly amazing that more mid-air collisions were not encountered. The statistics, although good under the circumstances, were hardly comforting to the aircrews as they blindly "bored up through the shit.”. Typical of these climb-out problems, on March 11th [1944], S/Sgt Eulon C. Bell, Tail-Gunner on Capt. Clifford D. Gohdes' aircraft, "hit the silk" when he thought his ice-covered Marauder had slopped into a spin as it nosed down north of Thetford, England.

Once on top, the Pilot and aircrew had to find the leader in a sky that could be filled with hundreds if not thousands of aircraft milling around and filling the sky with identification flares. Making the "on top" rendezvous especially hazardous was usually poor visibility, coupled with intermittent layered clouds or cloud build-ups. More often than anyone liked, aircraft would arrive on top and then not be able to locate their unit and have to return to base.

– John O. Moench, Maj. Gen., USAF, Marauder Men, p. 152.

By the end of August, four Marauder Groups were operating out of England: the 322nd, the 323rd, the 386th and the 387th. Arriving with the worst of reputations and a skepticism that the aircraft would never make it in the rough northern European combat environment, the experience to date was leading to a reassessment.

To the south, Gen. Brereton was secretly advised that the Ninth Air Force Headquarters, including the bomber and fighter commands, were to be transferred to England to take command of the tactical air elements of the Eighth Air Force. Marauder operations were obviously heating up.

In the meantime, those who kept and pondered over statistics were now calculating that the survival rate for a B-26 aircrew was 37.75 missions compared to 17.74 for a B-17 aircrew.

Contributing to these differences were the enemy tactics that led to a concentration of fighters on the heavy bombers while, in most cases, avoiding Marauders. On the other hand, the B-26s, flying at much lower altitudes than the heavies, were better targets for the German flak gunners, particularly those fierce 88 MM guns whose most effective zone of fire was considered to be between 10,000 and 20,000 feet. (Many aircrews of the heavies would hold to just the reverse, alleging that their higher damage to flak resulted from their higher altitude making them a better target.)

– John O. Moench, Maj. Gen., USAF, Marauder Men, p. 60.

[Comment on this passage: The Marauders didn't penetrate as far as the heavies and so were over enemy territory for less time per mission; comparing survival rates on a "time over enemy territory" basis eliminates much of the difference.

As to the concentration of fighters against heavy bombers: shorter penetrations also meant that there was less time for enemy fighters to respond and that it was very difficult to send the same fighters against the same mission twice, as was done for the heavies (once on the way in, once on the way out). Shorter penetrations also meant better escort coverage. Finally, the B-26s were smaller and faster; the handling characteristics that made them harder to fly also made it harder for an individual fighter to make as many passes against them (although the lower altitude of the mediums did give the fighters an additional advantage on their initial attack).]

APPENDIX 3 387th BG

:https://www.asisbiz.com/il2/B-26-Marauder/387BG-Chronology.html

387BG Mission:268 | Target: Mayen railroad bridge | Dec 23 1944 |

387BG Mission:269 | Target: Prum defended area | Dec 23 1944 |

387BG Mission:270 | Target: Nideggen railroad siding | Dec 24 1944 |

387BG Mission:271 | Target: Irrel highway bridge | Dec 25 1944 |

387BG Mission:272 | Target: St. Vith road | Dec 25 1944 |

Fri, 22 Dec 44 https://387bg.com/387th%20Bombardment%20Group%20-%20Chronology.htm

Fighters fly a few strafing, weather reconnaissance, intruder patrol, and alert missions; bad weather cancels all other missions.

Sat, 23 Dec 44 – Mission: Mayen railroad bridge

Sat, 23 Dec 44 – Mission: Prum defended area

In Germany, around 500 B-26s and A-20s attack rail bridges, communication targets, villages, a rail junction and targets of opportunity losing 31bombers; fighters fly bomber escort,...

Meanwhile the planes, after being grounded for several days by heavy fog, took off on December 23 to get the Mayen railroad bridge, an important link in the enemy’s supply system. Ordered to bomb by PFF, the crews foundCAVU conditions in the target area and scored, as was learned later, four excellent and one superior out of seven flights. Just after crossing the bomb line en route to the target, the formation was jumped by fifteen to twenty-five ME-109s, who concentrated on the low flight of the second box and knocked down four ships—those of Lieutenant W. O. Pile, W. N. Church,C. O. Staub and W. J. Pucateri. Partial compensation for this loss was

the destruction of four ME-109s and four damaged by Technical SergeantJoseph Delia, Staff Sergeant D. D. Fasey and Sergeants James Jones, Ed Wesolowski and Leo Mossman. The other flights, after the Germans had been beaten off, continued to the target through intense and accurate heavy flak and destroyed the bridge. The fifth plane was lost when LieutenantSmith’s plane was picked off just before “bombs away.” In returning to the field Lieutenants W. P. Wade and T. G. Blackwell were forced to crash-land their badly damaged ships.

– History of the 387th Bombardment Group (M) AAF, p. xxx.

Just preceding Christmas Lieutenant Don Whitsett had flown his seventy-fifth mission in”Mississippi Mudcar” and had departed for the States. This plane was one of the original B-26s which had been ferried across the north Atlantic in June 1943; Lieutenant Whitsett had flown in it as co-pilot. On December 23rd the “Cat” was shot down on its 150th mission.

– History of the 387th Bombardment Group (M) AAF, p. xxx.

Finally, on December 23rd, the weather over the Bulge area cleared and fighters and bombers from both the 8th and 9th Air Forces literally swarmed over the battlefield. The Luftwaffe was also out in a surprising show of strength.

The initial target of the 387th was the railroad bridge at Mayen, Germany, approximately 25 miles west of Koblentz, which carried a critical rail line to the battlefield.

Our losses for the mission were seven of the thirty-six aircraft which were launched. The target for the afternoon mission was Prum, a communications center approximately 35 miles east of Bastogne.

…

On the 23rd of Dec., 1944, the first day that we could launch a mission in the Battle of the Bulge,

I flew as a substitute co-pilot on both the Mayen and Prum missions. During the former, our a/c was in one of the wing positions in the first box and except for the excitement of finally being able to join in this critical battle, it was a fairly routine mission from my standpoint.

When we reached our fighter rendez-vous the escorting fighters failed to appear and, as briefed, the leader turned on course over Bastogne.

We didn't realize it at the time, but for some reason our second box missed the turn and became separated from us by five or six miles. In addition, their low flight was lagging behind the box leader.

This violation of formation discipline resulted in a flight of ME 109's effectively attacking the low flight and shooting down four of the six a/c. In the first box, although we were aware of enemy fighter activity by the radio chatter, no enemy aircraft were in view from the cockpit. Flights in the first box approached the target in a routine manner, went into their in-trail formation and scored excellent results on the bridge. The flak was accurate and heavy, but no a/c were lost over the target.

In the meantime, the second box was engaged in a running gun battle with the ME 109's until one minute prior to opening their bomb bay doors.

The two surviving Marauders from the low flight had tacked on to the lead flight.

The Box Leader, realizing he was approaching the target on a heading different that that which had been briefed, made a 360° turn and lined up properly for the bomb run. The high flight followed him and the two flights made long steady runs and dropped with excellent results.

Both boxes sustained further flak damage on the way out, losing another aircraft and two aircraft crash landed at the base. Photos showed one span of the bridge destroyed and another span partially destroyed.

Within a few minutes after climbing out of the a/c, I was in a truck going to the briefing tent in preparation for a mission over Prum, Germany, a communications center for the German ground forces attacking in Belgium. As a substitute co-pilot for one of our Flight Commanders, I had more battle-time to observe the intense aerial activity over the area of the battle.

Our group was at 10,000 to 15,000 feet—the B-17's and B-24's were above us, probably at 20,000 to 25,000 feet and flights of P-47's could be observed peeling off below us in dive bombing and strafing attacks.

Prum was about thirty five miles northeast of Bastogne and I recall the flak was especially accurate as we flew toward the target. Regardless of our evasive action, the bursts seemed to be all over us. As our flights manoeuvred into their in trail formation to commence the bomb run, the flight of six ships ahead of us from another group, literally blew apart. I presume the lead ship received a direct hit and the other five aircraft banked away to his right and left.

The 387th had been able to launch only 26 aircraft for this mission instead of the customary 36, and 21 of the 26 received battle damage. The bombing results were excellent.

– Paul Priday (556th B.S.), Mission to Mayen.

The 387th Group lost four bombers and a pathfinder to some 20 German fighters that blasted away at the B-26s between Bastogne and their target at Daun...

In the hit on Mayen, the 387th suffered the loss of four Marauders to enemy fighters and another two to flak after failing to find their escort from the 367th Fighter Group.The B-26s did, however, claim 4 German fighters downed.

– Daniel Parker, To Win the Winter Sky, pp. 234.

The 387th and 394th BGs hit the village of Prüm east of St. Vith. The 387th lost only one plane due to flak damage. The crippled bomber wash it just before the bomb run and suddenly arched over on its back. The pilot somehow managed to roll over and straighten out in time to drop its bombs before the B-26 fell off to the side and spun to the ground...

– Daniel Parker, To Win the Winter Sky, pp. 235-236.

Staffeln of JG 11 opposed the 70 B-26 Marauders of the 387th and 394th BGs bearing down on the marshalling yards at Mayen.

– Daniel Parker, To Win the Winter Sky, pp. 243.

….

Mon, 25 Dec 1944 – Mission: St. Vith road

Nearly 650 B-26, A-20s and A-26s hit rail and road bridges, communications centers and targets of opportunity in W Germany and the breakthrough area;...

Following the attacks on Prum and Nideggen the Group, on Christmas day, amid hail and snow, went after the Irrel road junction. On this mission occurred one of the most heroic incidents in the history of the Group.

The lead plane of Lieutenant John A. Alexander of the low flight was hit hard by flak over Bastogne, four minutes from the target. Two minutes later the interphone was shot out and a few minutes after the intervalometer.

Since the time remaining was too short to make the necessary adjustments,Lieutenant Harvey W. Allen, the bombardier, signalled to the pilot to make another bomb run. With rudder, ailerons and wings full of holes, Lieutenant Alexander managed to hold the plane level so that the bombs could be salvoed, hitting inside the target area.

Losing altitude fast and perceiving an indicated air speed of only 160 mph, Lieutenant Alexander coaxed his ship back across the bomb line near Trier and ordered the crew to bail out.Seven of the nine aboard made the jump, but staff Sergeant Michael Aguilar was thrown against the radio table and his chute flew open.

Lieutenant Alexander gallantly offered to try to crash land the plane, but SergeantAguilar gallantly refused to agree, realizing the impossibility of a crash-landing among the hills. Climbing gingerly down through the nose wheel with the parachute draped over his arm, Sergeant Aguilar successfully made the jump.

At 700 feet Lieutenant Alexander bailed out and watched his plane crash into a small creek and explode. They were not yet out of danger, for someAmerican soldiers, thinking they might be Germans, fired at them before they could identify themselves.

For their acts of gallantry, Lieutenant Alexander was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal and Sergeant Aguilar the Silver Star.

In the afternoon a 387th formation attacked St. Vith with excellent results, but the most exciting events of the day were to happen after the mission.

A 397th plane, coming in after dark, hit short of the runway, burned and exploded. The twenty-eight 100 pound demolition bombs knocked out nearly all windows, both on the base and in Clasteres. Fortunately all the crew escaped.

About twenty minutes later a 387th plane, returning with sixteen 250’s from a test flight, came in. In landing the nose wheel tire was punctured by a bomb fragment from the 397th ship, the 387th plane nosed over, caught fire and exploded.

This crew also escaped, but all other whole window panes in Group headquarters were shattered.

– History of the 387th Bombardment Group (M) AAF, pp. xxx.

Came a never-to-be forgotten Christmas Day. In the morning the target was a road junction at Irrel. Ground in the target area was blanketed with freshly fallen snow, and have made bombing more difficult. Nevertheless, most of the formation hit the target for good results, and the rest bombed the defended town of Echternach; also with good results. Making a secondary run on the primary target, the ship of Lieutenant [John] Alexander, leading the Low Flight of the II-Box, was hit hard by Flak, knocking out his one engine and the bombsight. Lt. [Harvey] Allen, bombardier, ingeniously go this bombs away in the target area, nonetheless, allowing his flight to bomb.

In turning off the target, the ship was hit again and again by Flak; the rudder being badly damaged, both left gasoline tanks punctured, the top turret smashed and the nose Plexiglas of the plane shattered.

Lt. Alexander kept the ship under control while Lt. Allen and Sgt. Miller,GEE Operator, directed him to friendly territory, where all nine men in the crew safely parachuted. S/Sgt. Aguilar jumped after his parachute had opened accidentally inside the aircraft, and Lt. Alexander, last man out, with difficulty jumped from the careening plane at 700 feet. The plane was seen to crash seconds later into the bank of a small stream. All of the men returned later. None of the remaining nine planes furnished by the squadron received damage.

– 556th Squadron, MonthlyReport, December, 1944.

On the Group's morning mission to Irrel, Germany, 1st Lt. John A. Alexander- 0699645, by his undaunted actions, earned our country's second highest honour for valour, the coveted Distinguished Service Cross.

– Peter Crouchman, Alan Crouchman,Robert C. Allen, William J. Thompson, Jr., 556th Bomb. Squadron, B-26Marauder Reference and Operations Guide, p. 52.

1st Lt. James M. Neff was our crew's pilot, and I might add, a damn good one. His skills were certainly taxed to the limit during the afternoon mission to Saint Vith, Belgium on Christmas day.

After waiting most of the morning for a special mission, which did not materialize, our six plane flight was tacked on to the Group's second mission.

The I.P. was the town of Malmedy, approximately twenty-eight miles north of St. Vith.

The target was heavily defended, and the scene of much Allied aerial efforts to disrupt German traffic in the area. We had a fresh snow fall on Xmas morning, the first of that cold winter. The visibility over the target was excellent, and each flight bombed visually.

I was in my gun position as tail-gunner, as our flight levelled out for the bomb run.

Lt. Vernon Briscoe was calling last second corrections.,when our plane seemed to shudder. The next second, I saw the planes in our flight do what I thought was a climbing right turn. This brief recollection lasted only a millisecond before I realized our plane was descending fast in a steep left turn.

I saw smoke coming from one of the engines and called Neff on the intercom. His calm reply was, "I know it." He called Gamble to come forward, "On the double." I then saw that the left wing had holes in it, as well as the tail section. Neff adroitly managed to control our descent, and told the crew to standby to bail out.

I grabbed my chest pack and met Walt Simmons (AG-top turret gun.) at the waist gun window. Walt plugged into the waist window intercom as I made ready to jump.

43-34303I learned later... that when Gamble went forward, he waded through ankle deep gasoline in the aft bomb bay. He notified Neff of this potential danger.The pilot's compartment was a shambles. Jimmy Harris, our copilot, was bleeding from shoulder and face wounds, the plexiglas was shattered and the pilot's instruments were shot out. Neff had his hands full trying to maintain control of our aircraft's descent. Bris and Lt. Russ Trapper, our navigator, along with M/Sgt. Paris "Hoop" Hooper, our GEE operator, were feverishly, but methodically, plotting our position, and relaying headings for Neff to steer in order to be over friendly lines.

The left engine seized up and Neff feathered it, when Harris announced that our right engine had burst into flames. The danger was very great for a midair explosion, and Neff and Gamble realized it.

At the persistent coaxing of our calm bombardier, Neff delayed the bail out order until Bris assured him we were over our lines. Neff ordered Trapper and Briscoe out of their nose compartment, and then gave the order to bail out. Walt and I exited the flaming aircraft from the waist window, while the other six members used the open bomb bay. Neff was the last member of the crew to jump.

The B-26G circled under him, and then exploded in mid air!

The fuselage fell into the Meuse River near Huy, Belgium, while its two engines fell on each embankment.

Four of us descended by parachute into the front-line positions held by the 84th Inf. Div., where we ate our Xmas supper.

Harris ended up in a Paris hospital, and the rest of us arrived back to the 387th BG within three days. I suffered injuries to my ankles, while Bris was crippled with a knee injury. Luckily, no one else was injured. On board were:

– Peter Crouchman, Alan Crouchman, Robert C. Allen, William J. Thompson, Jr., 556th Bomb. Squadron, B-26Marauder Reference and Operations Guide, p. 61.

Lieutenant Harvey Allen, bombardier on Lt. John Alexander's lead crew, suffered facial lacerations when the B-26 Plexiglas nose was shattered during their initial bomb run over Irrel.

Lt. Allen reported that his bomb sight was also damaged by the flak. On their flight's second bomb run, Lt. Allen aligned the secondary target up visually and they were able to place all their bombs in the target area. For his actions, 2nd Lt. Harvey Allen was awarded the Purple Heart and the Silver Star.

Staff Sergeant Michael C. Aguilar's rip cord caught on the radioman desk in the confined compartment of their stricken plane. His parachute prematurely popped open as the crew were making their emergency exit from the Marauder. When Lt. Alexander saw Aguilar's plight, he offered to stay with their falling plane and attempt to make a crash landing in the mountainous terrain, in order to give his engineer a chance for survival. The airman realized the great risks of Lt. Alexander's offer. It was then that Anguilar (it is reported) picked up his unpacked parachute, draped it over his shoulder, and exited through the nose wheel. Fortunately, his parachute and shroud lines performed perfectly and he floated to earth safely. Lt. Alexander was right behind him. To add to their hectic experience, friendly infantry men opened fire on them when they landed.–

FW Supplemental Section,Personal Experiences & Anecdotes By And Of The Men Of The 556th Bomb.Squadron, p. 52-A.

[This account reports that the flight was attacking the secondary target;this is probably incorrect.]

When the aircraft suffer edits initial flak damage, Mike Aguilar, Engineer/Gunner, came forward from his position in the top turret to assist in the cockpit. As Mike passed through the bomb bay the ripcord of his chest pack parachute was snagged and the chute was accidentally opened. After "Bombs away," when it became apparent that the aircraft would have to be abandoned, John gave the order to bail out.

As John struggled to control the rapidly descending "June Bug," crew members exited the aircraft until only John and Mike remained. At that point they were faced with an agonising decision. As aircraft commander, John was duty and morally bound to attempt a crash landing if Mike was unable to jump. If Mike elected to gather his opened chute in his arms and exit the aircraft, he faced the very real possibility that his chute would prematurely deploy and snag on some portion of the aircraft, carrying him to certain death. Another possibility was that the canopy would become twisted or entangled in the shroud lines and fail to properly deploy.

Considering the uneven terrain over which they were flying, an attempted crash landing was a questionable alternative. Mike decided that he would jump rather than risk both of their

lives. Miraculously, Mike's parachute deployed and he landed safely. John exited the "June Bug" as soon as possible after Mike's departure and, though perilously close to the ground when his chute opened, survived the touch-down.

For his heroic act of unselfishness,Mike was awarded the Silver Star. So was Harvy Allen, Bombardier, who had gallantly effectively directed the successful bomb run after the nose section had been seriously damaged by flak.

General Orders No. 53

John A. Alexander O-699645,First Lieutenant, Army Air Forces, United States Army. For extraordinary heroism in action against the enemy while serving as pilot of a B-26 aircraft in a daylight bombardment mission over Germany, 25 December 1944. On this date, during the initial approach to the target, flak damage severed communications between Alexander and his bombardier and since contact could not be reestablished in time for accurate bombing Lieutenant Alexander continued to lead the flight on a true and level course. Midway on the bomb run another flak burst destroyed the bomb sight, shattered the plexiglass and tore holes in the wings and rudder. In spite of the great damage sustained by the aircraft, Lieutenant Alexander continued on an accurate course over the target and bombs were released with excellent results. The extraordinary heroism and determination to complete his assigned mission displayed byLieutenant Alexander on this occasion are in keeping with the highest traditions of the Armed Forces of the United States.By Command of General Spaatz

On 25th of December 1944 the 387th was assigned to hit the target atSt. Vith in the bulge. We misidentified the target and hit a small town a few miles away. That small town just happened to house the headquarters for the German General who commanded the German forces in the bulge. That general wrote an article that appeared in Life magazine in December of1945 wherein he suggested that our mistake crippled the effectiveness of his headquarters. I hasten to add that the first two boxes of the 387th did hit St. Vith, but my box did a 360 degree turn at the I.P. to provide better separation, and lost sight of the first two boxes. I read the article in Life waiting to get a haircut. I would love to have someone find a copy of the article and make it available. Please e-mail me. Thank you.

Thomas C. Britton, Major, USAF (Ret’d)

APPENDIX 4: 322nd BG

http://www.historyofwar.org/air/units/USAAF/322nd_Bombardment_Group.html

History

The 322nd Bombardment Group was a medium bomber group that had a disastrous introduction to combat in the spring of 1943, losing ten out of eleven aircraft on its second raid, but that went on to develop effective medium level medium bomber tactics and supported the Allied armies after the D-Day invasions.

The group was formed in the United States in the summer of 1942. It was equipped with the B-26 Marauder and would use that aircraft throughout the war. The group's ground echelon began to cross the Atlantic in November-December 1942, followed by the aircrew and aircraft in March and April 1943.

On 13 May 1943 the group was declared operational, as part of the Eighth Air Force. This was the day that saw the 4th Bombardment Wing enter combat, and the available aircraft strength of the Eighth Air Force rise from 100 to 215 as the US build-up began to gather pace. Its first combat mission came on 14 May and was an attack on a power station in Holland. This first low level attack was successful, but a second low-level attack on 17 May was a total disaster. Eleven aircraft were sent on the raid. One returned early, but all ten that pressed on to their target were lost, shot down either by anti-aircraft fire or by German fighters.

After this disaster low level medium bomber operations were suspended. The group spent two months training to operation from medium altitude, before returning to combat on 17 July 1943. The new medium level tactics were more effective, and were tried out against German airfields between July 1943 and February 1944. The group was awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation for the period between 14 May 1943 and 24 July 1944, reflecting the success of the new tactics.